Just built this in 8 hours with AI

Ai is wild. It only took me about 8 hours to build a full web app from scratch. Check this Upstate SC Wedding Directory out.

The Architect's View: Software & Strategy

Navigate Complexity, Lead with Vision, Architect Success

Ai is wild. It only took me about 8 hours to build a full web app from scratch. Check this Upstate SC Wedding Directory out.

Google has spent more than a decade and a significant amount of money determining how to create high-performing software teams. Incredibly, they have published their findings in a free document called the DORA report, which I have leaned on heavily in writing this article.

There is a huge difference between high and low performing teams, for example the highest performing teams have 127x faster lead time and 8x less change failures on average compared to low performing teams. One fantastic bit of news is that teams can change performance; Google found in the DORA report that teams become elite through continuous improvement and most elite teams started as average teams. To me this is very encouraging because we can take an average team and turn them into an elite team, thereby gaining multiples of speed improvement and huge reductions in deployment failures.

Not only does Google’s DORA report tell us that teams can make huge performance changes over time, but it also gives us some hints as to how leadership can promote these changes.

Vision – The leaders must set a direction and clearly layout goals

Inspirational Communication – Effective leaders make team member proud that they are part of that team through maintaining positive communication about the team and it’s direction.

Intellectual stimulation – Leaders present the team with new challenges and encourage the team to continually consider new ways of looking at old problems.

Supportive leadership – The best leaders have empathy and consider the feelings of those around them.

Personal Recognition – They publicly recognize superb work.

Each of these pillars is a deep topic in its own right, full of practical techniques and common pitfalls. That’s why, over the next few posts, I will be publishing a deep-dive on each one, turning these concepts into a concrete action plan for you and your team.

To ensure you don’t miss this series, follow me on LinkedIn. Or on my website at matw.me I’ll be starting next week with a deep dive into creating a team Vision that actually inspires.

Which of the five fundamentals do you think is most overlooked by leaders today? Let me know in the comments!

Does this sound familiar? Your team wants to make a simple change to the codebase, it should be simple anyhow, but you realize that instead of being a simple task, it’s going to take 2 engineers a week to make the change because of some complexity or lack of a solid deployment pipeline. This is not a one off occurrence, but you find it happening frequently.

Or maybe you are able to make quick roll outs, but you fear deployment day because of past regressions or worse maybe even an outage. These are completely avoidable scenarios, but without a solid plan, these are inevitable outcomes.

Tech debt shows itself in many ways, inflexible code where new features take a long time to develop and deploy, fragile code that has constant regressions, infrastructure that does not scale well with increasing demand, and even difficulty onboarding new team members. Tech debt is not always obvious, especially to those who are even slightly removed from the stack, instead of being a big obvious issue, it show up as diffuse and difficult to spot slowness and general issues. Its not like broken leg, where the reason you can’t run is obvious, it feels more like you are running on loose sand, you and your team are putting in effort, but little progress is being made. This is tech debt, well at least the symptoms of it. So if this is the symptoms, what is tech debt actually?

A teams tech debt is almost never one thing, but it’s a gradual (and inevitable if not planned for and dealt with) accumulation of small hinderances, typically introduced to save time in the moment in exchange for time cost in the future. Sounds a lot like financial debt actually doesn’t it? Anyway, sometime choosing a faster solution today that will cost time in the future is the correct choice. In fact, the most expensive option for now is almost never the correct choice even when it create efficiency in the future. Let me provide an example: Let’s say we are building a simple app that once we deploy it in the next couple weeks, we don’t expect to update it frequently, we could spend a few days creating a deployment pipeline that is fully automated after a git merge to the default branch. This would be very efficient in the future whenever changes were made, but since it will take a couple days to create this, and the fact that we don’t expect to make many changes, we should probably be willing to live with a manual deployment process even if this requires copying some files to a server manually or whatever the case may be. So that would now be tech debt, because in the future we know that it will take maybe 30 minutes or an hour to deploy changes instead of 10 seconds. Although this is tech debt, it probably acceptable. Now let’s consider how this acceptable tech debt could become unacceptable. Say this app becomes extremely popular, and as it becomes popular, new feature request start coming in weekly, also some of these new features add more services that require deployment and updating whenever releases are made. Now, a year later, the dev team is spending 3 hours a week just on deploying this app, furthermore deployment days are often met with a broken environment because someone forgot to update one of the now dozen services that this app now relies on. So what was one an acceptable compromise is now a burden, it has become significant technical debt and its costing the team time and customers will become frustrated with the unreliability. However, the team and company have become custom to this problem now and don’t even recognize it as tech debt, its just the way it is. A bit like the frog boiling in the pot as the heat slowly increases and therein lies one of the biggest problems with tech debt, it’s not always obvious as it slips in slowly.

Technical debt is a hidden roadblock that hinders team progress, effective leaders must recognize tech debt and advocate for its removal while implementing a strategy and creating a culture that will clear the path for future innovation, velocity, and creativity. However this approach must be pragmatic and recognize that resources are finite, so strategy and prioritization are important.

As mentioned earlier, tech debt slowly creeps in, this makes it difficult to recognize. Effective leaders must look for and recognize the roadblocks that are slowing your team down.

Once areas of tech debt have been spotted, the leaders next step should be to quantify the debt. Start by outlining the teams roadblocks, and then do a deeper investigations to determine and quantify the cost of the tech debt. Continuing with our previous deployment example, one could track how much time was spent monthly running deployments and compare that to how long deployments should take with an ideal pipeline. If your team spends 12 hours a month running deployments that could be fully scripted, then spending 40 hours to create a build pipeline is an obvious win since that time will be fully recouped within a few months. Not to mention a script is much more reliable than any hand run process.

Let’s look at another area of tech debt that is frequently overlooked or not recognized as tech debt, documentation. Without proper documentation, it is difficult to onboard new engineers. New engineers will also be frustrated when presented with a wall of new code, but no proper onboarding documentation or architectural overviews to help guide them. Best case scenario is that they reach out to another team member who spends time answering questions and helping onboard the new dev, but often this will only happen after the dev has spent hours trying to figure it out themselves. Furthermore, it could degrade the confidence of your new hires. Having proper documentation in place will make your team look professional to new hires, prevent frustration, and save countless hours. Proper documentation not only helps with new hires, but helps team members rotate through different projects efficiently, and helps refresh memory when devs come back to a project after some time. Proper documentation cannot replace good employee retention, but turnover is inevitable and having the documentation will help with loss of knowledge when team members leave. The leaders role is the same as with other areas of tech debt, he must recognize issues, put in place a plan for mitigation, and advocate for better documentation going forward.

Not everything can be planned for and the concept of “you are not going to need it” (YAGNI) is also sound. So I’m not advocating for always having the most sophisticated build pipelines and I’m not saying that a few manual deployment steps here or there are not permissible, but leaders have to be the voice of reason. The more a bit of code is touched, the better the pipelines must be for deployment. Documentation is always important. To be continued in a future part…

Nearly every online application will need authentication and almost every page / feature of most applications will need to be locked behind the authentication wall. Since auth is so tightly integrated throughout an application, it is important that it is well abstracted, fast, and seamless. Authentication is basically “prove to me who you are” it’s kind of like showing your ID to a bank teller, or using your ID to gain access to your place of work. Authentication is closely related to the concept of authorization, but they are not the same, and thinking of them distinctly is important unless you have a basic application.

If having an ID is analogous to authentication, then having a key is analogous to authorization. You can be authorized to access something without being authenticated. Also you can be authenticated, but not authorized.

Examples:

Authenticated, but not authorized – If John Doe goes to the bank and shows his ID to the teller and tries to access money from Mark Moe’s bank account, the teller will say no of course. He is authenticated (as John Doe) but not authorized.

Authorized, but not authenticated – John Doe has tickets to a baseball game. When he enters the stadium, they take his ticket, but do not need to see his ID.

Software authentication typically uses one of following:

Probably the most common web authentication that users see is the password input, that uses something you KNOW to prove your identity. Some apps will use something you know for initial authentication, an example of this would be an online loan application.

Fingerprint scanners and face recognition are becoming popular on phones and laptops and use something you ARE to authenticate you.

When application message you a 6 digit code to your phone or email, they are using something you HAVE to authenticate you. Another example of something you have is a hardware authentication device.

Users will encounter authentication early and often when using your application, therefore it’s important to make it simple and easy to use. Later on in larger applications, the different services within your application will need to authenticate and/or authorize with each other often so a well abstracted auth mechanism is important there as well. Develops should give adequate attention to a smooth and simple to use authentication method that is also secure enough for the application.

The previous post showed how to select and edit every paragraph element on a page adding a smiley face to each paragraph, but we run the code by entering it directly in the Javascript console. How can we run a section of JavaScript code when something happens? Often we want a section of JavaScript code to run when a button is clicked. Let’s see how that is done.

Note that I am ignoring some best practices for the sake of simplicity.

Let’s add a button to our page using, <button>CLICK ME</button>. When we click the button, nothing happens.

Let’s say you got here and want to follow these instructions, but don’t know how. You can edit, create, and run HTML / Javascript code and html sections at: https://codepen.io/pen/

Well that does nothing and is pretty boring, so let’s make it do something.

Starting simple let make the button trigger an alert. Change the button code to:

<button onclick="alert('You clicked the button')">CLICK ME!</button>

to get this:

If you click on the button, you should get an alert box.

Now let’s make a button to add 🙂 to the end of each paragraph.

From the previous post we have this section of code that appends 🙂 to the end of each paragraph on a website.

allPTags = document.getElementsByTagName('p'); // Gets all our p tags

for (let pTag of allPTags) { // Loops through each p tag

pTag.append(' :) '); // Add :) to each P tag

}

Let’s take this code block and smash it inside our button.

<button onclick="

allPTags = document.getElementsByTagName('p'); // Gets all our p tags

for (let pTag of allPTags) { // Loops through each p tag

pTag.append(' :) '); // Add :) to each P tag

}

">CLICK ME FOR SMILES!</button>

OK, I know this is really ugly, but it’s simple and it will work! We can clean this up in a later post.

Here is the result:

Click away! You will see that every click adds more smiles to the page!

The console and inspector were essential to me as a beginning developer and after 10 years experience I still use it almost daily.

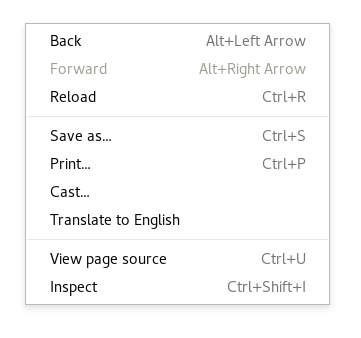

First step (using Chrome) right click on your screen. Anywhere within the browser should work. A dialog menu box should appear.

Click the “Inspect” button to open Chrome devTools.

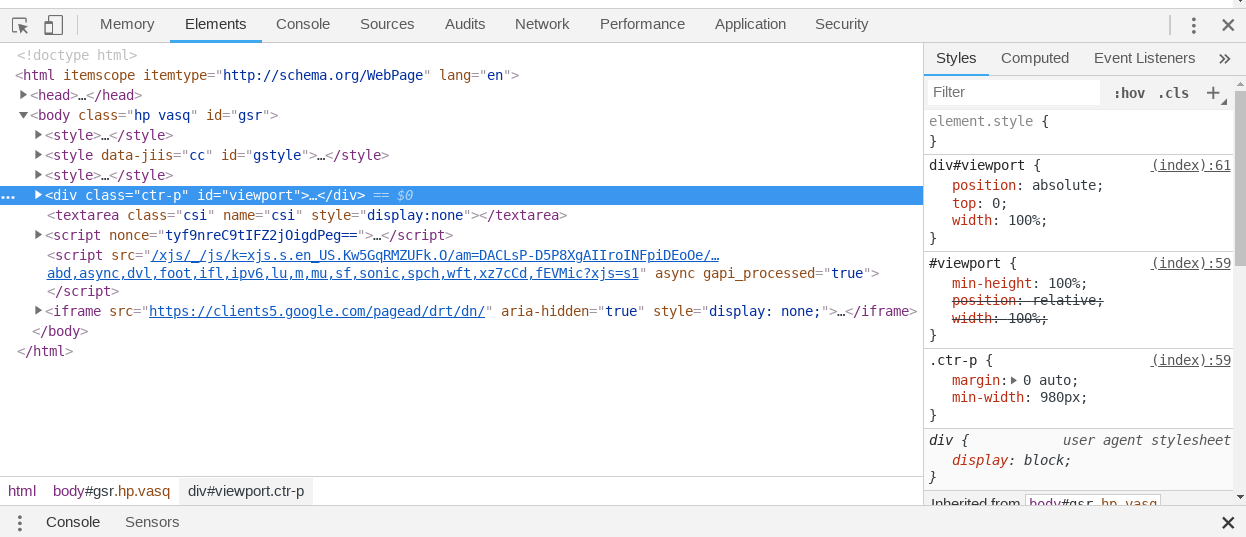

The inspector has multiple tabs, we are interested in the “Console” tab.

After clicking on the Console tab, you may see some text, errors, or other messages. Some websites even have hidden Easter eggs in the console. The important bit is that you can execute Javascript code here. For example, click just to the right of the > sign and enter 2+2, followed by enter. This should output the correct answer of 4. You can also do subtraction, multiplication 5*5, division 10/5, and a special one called modulus which gives you the remainder after a division operation. For example, 10%2 would equal 0, since there is no remainder, but 10%3 will return 1, since the “remainder” of 10 divided by 3 is 1.

So you saw how you can use the console tab as a calculator, but there are some strange things that can happen here. Check this out, add 0.1 and 0.2. Now I’m sure you can do this in your head, but go ahead and enter it into the console 0.1 + 0.2. You would expect the result 0.3, but it actually outputs something like 0.30000000000000004. Strange, isn’t it? This happens because Javascript uses floating point math. In short, it cannot accurately store nonintegers like 0.1. The math is close, but not exact.

They are a ton of great resources online to help get you started on your learning path.

Check out ” How to Learn JavaScript Properly” for encouragement and ideas for learning with others.

Also check out Alex Devero’s blog for learning and study tips.

Do you know any other weird parts of Javascript? If so, tell about them in the comments.

Strings are sequences of characters. In the previous post, we saw how to open the Chrome devTool inspector panel. In the console tab, we can enter numbers and use the console as a basic calculator. When dealing with numbers in Javascript, we do not place quotes around them, but when entering strings, they must begin and end with a quotation mark. The quotation mark can be a single ' or a double " quotation mark. For example, to create a string with the text Hello World, type "Hello World" into the console then the return key to execute. This will cause the string "Hello to be repeated in the console. What’s happening here is the line is actually read in, then Javascript produces an actual string and then returns it. This returning of the string is what produces the second output of

World""Hello. The string is returned, but it is never saved, so it just vanishes in this example.

World"

Well, the previous example was not very useful – a string is created and then vanishes. To improve on this and do something a bit more useful, we need to save the string somehow. This is done by declaring a variable and the string as the variable’s value. Variables are declared with the keyword var followed by the variable name. For example, to declare a variable named myString, type var myString followed by enter. This will create a variable, yet the variable has no set value. The equal sign is used to set the variable’s value and the syntax to set a string value looks like variableName = “value”. So for our example, setting myString to Hello World, type myString = "Hello World" followed by enter. It is possible to combine the variable declaration and setting into one command like this var.

myString = "Hello World"

OK, so the variable is declared and set, but it’s still not useful unless we can do something with the variable. Let’s declare one more variable named, myName and set it to “My name is ______” but go ahead and put your name there. So for me, it would look like var myName and then enter. Next, let’s put the two strings together. This is called concatenation. This is done using the + sign. Technically the + sign here is an operator, as it performs an operation. So putting the two together looks like

= "My name is Matthew"myString + myName. Go ahead and try it. Well, that’s not quite correct – it returns “Hello WorldMy name is Matthew”. That’s pretty close, but some spacing would help us out. Let reassign (update) the myString variable. Let’s add a period and a space to it. This can be done by simply reassigning it as myString = "Hello World. ", but I’m lazy and don’t want to retype “Hello World” again. Instead, I can use a special operator call the concatenation operator which looks like +=. The += operator concatenates two string variables together and updates the first variable to the concatenated string. An example should help clear that explanation up. So continuing with our previous example, to update myString by adding a space and a period, we can simple use myString . Don’t leave out those quotes! So if we did all that correctly we should be able to do

+= " ."myString ENTER and see “Hello World. My name is Matthew”.

+ myName

Let’s try something fun. In your Chrome devTools console, enter document.title = "Kittens". Now look at the top of the browser, and look at the tab title for the site. It now says Kittens. You just updated the document title with a new string.

So you now can “hack” and change the title of a website. Do you know any other string hacks? Leave a comment if you do.

Previous posts have covered strings, numbers, and arrays. Arrays can help organize related strings and numbers into a list-like behavior, but finding items in the list can be a bit difficult. Javascript offers one more method to organize data called an “object”. Objects store and retrieve items using a key – value system. For example, if you had an item located somewhere in a room full of lockers, you might tell someone to go and get me the contents of locker 15. In this example, the key is 15. Another example might be a phone book or encyclopedia (ancient relics of the past), where the key would be the subject title or person’s name and the value is the content.

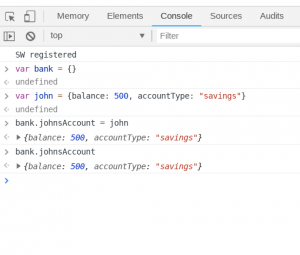

Ok, let’s go back to the console to look at this concept first hand. (First post covers opening the console) Let’s create a new object called “bank”. Enter the following into the console var. When you press enter, it will create a new object and store it as a variable named bank. To verify this, you can type bank and hit enter. The console will show you a set of brackets like {}. Now, most banks have accounts, so let’s add a few accounts to our bank. Good news, our first customer John just walked in and created a new savings account with $500. So we need to store at least two bits of information about John’s bank account, the balance, and the account type. For our bank, we need to store multiple bits of information about each account, the best way to do this is by using an object.

bank = {}

As you just learned, objects can store string and numbers, but they can also hold other objects. With that in mind, let’s create a new object called John. But this time instead of creating an empty object, we will create the object with John’s account information. Similar to when we created the bank object, we will use the var keyword and a set of brackets, but our brackets this time will not be empty. We will add the object’s data inside the brackets and each entry will be delimited by a comma. Each item entry is a key-value pair with a colon separator. So for John’s account it will look like var john =. There are a few things here I want to point out, as I hope to prevent you from confusion. First, you should notice that the “Keys” balance and accountType are not in quotes; this is because they are the “keys” and in the same way that our object name “John” isn’t required to be in quotes, they do not need them either. Now it is OK to add the quotes and

{balance: 500, accountType: "savings"}var john = would be perfectly valid. Second, string values need to be in quotes, but numbers do not. So now we have an object called bank and an object called account, but this is not very useful yet because we want John’s account to be part of the bank variable.

{"balance": 500, "accountType": "savings"}

Now we need to add John’s account to our new bank. With John’s account, we added the values during the object creation, but we created the bank as an empty object. Now we can add John’s account object to our bank object. There are a few ways to add to objects, here I will cover “dot notation”. Adding a subobject to an outer object looks like outerObject.subObject = “value” keep reading a bit if that is confusing. Hopefully, our bank example will help. We already created our empty bank with

Now we need to add John’s account to our new bank. With John’s account, we added the values during the object creation, but we created the bank as an empty object. Now we can add John’s account object to our bank object. There are a few ways to add to objects, here I will cover “dot notation”. Adding a subobject to an outer object looks like outerObject.subObject = “value” keep reading a bit if that is confusing. Hopefully, our bank example will help. We already created our empty bank with var, now to

bank = {}

add John’s account to our bank with the key, “johnsAccount” we enter bank.johnsAccount. Great, now our bank has a new customer named John and we can access his account info using the same dot notation

= johnbank.johnsAccount This will return us John’s account details.

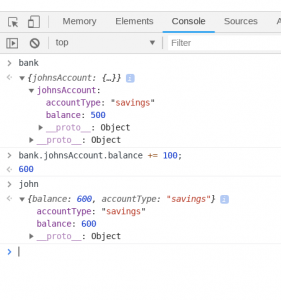

John just came back in and deposited an extra $100, now we need to update his balance, how can we do this? To update John’s account, we can use the dot notation to access his balance and update it. To add $100 we could set it to 600 using bank.johnsAccount.balance, but we could instead let Javascript do the math. There are a few special operators for add, subtract and other math functions. To add to a variable, we can use the

= 600+= operator. This is called the “plus assignment” operator. It’s called “assignment” since it does the math and reassigns the variable of the output. If we wanted to add 100 to the balance without using the assignment operator, it would look like this: bank.johnsAccount.balance =. However, using the assignment operator shortens the statement quite a bit to just

bank.johnsAccount.balance + 100bank.johnsAccount.balance += 100. Running this will update the balance by adding $100. There is also the -= assignment operator which works the same way, but of course, subtracts.

There is one strange side effect of changing the bank balance. We updated bank.johnsAccount.balance, but what about our original variable of john? It turns out that it gets updated too. Take a look, type john in the console and hit enter and you will see that john.balance has been updated. This is because bank.johnsAccount wasn’t just set to the value of “john”, it actually is a reference to the variable john. Updating one changes the other as well.

There is one strange side effect of changing the bank balance. We updated bank.johnsAccount.balance, but what about our original variable of john? It turns out that it gets updated too. Take a look, type john in the console and hit enter and you will see that john.balance has been updated. This is because bank.johnsAccount wasn’t just set to the value of “john”, it actually is a reference to the variable john. Updating one changes the other as well.

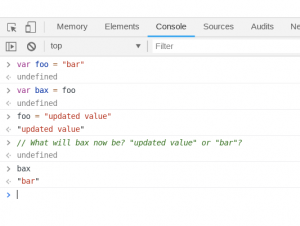

This is a special feature of objects, this same behavior is not repeated with string or number variables. For example, varfollowed by

foo = "bar" var bax = foo of course sets bax to the value of foo, which is then the string “bar”. You might think that changing foo would also change the value of bax, yet it doesn’t.

Can you think of some good uses for objects? Leave me some examples in the comments. Remember to practice what you are reading. When I was first learning, I could read and read, but it only “sunk in” once I practiced it. So go ahead and open up that console.

Until recently, using JavaScript meant was reserved strictly to building websites, but today, Javascript runs pretty much everywhere. That being said, the most common application for JavaScript is still to manipulate websites or make a web-based application. There are two ways that JavaScript code can be loaded and/or added to a webpage: inline scripts and external scripts.

Practicing these examples will help you start your journey of learning JavaScript. You will need a simple text editor to make your website files. Don’t use a word processor, because they adds hidden tags to format documents, and while these tags are useful for producing formatted documents, they are not compatible with HTML.

To begin, you can open a valid HTML file with your browser. There are a few ways to do this, and the easiest way is to right click the file and use “Open With” to open the file with a web browser. For more information, visit https://www.codecademy.com/articles/local-web-page

Let’s open our editor and create a basic webpage using the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello Javascript</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Webpage works!</h1>

</body>

</html>

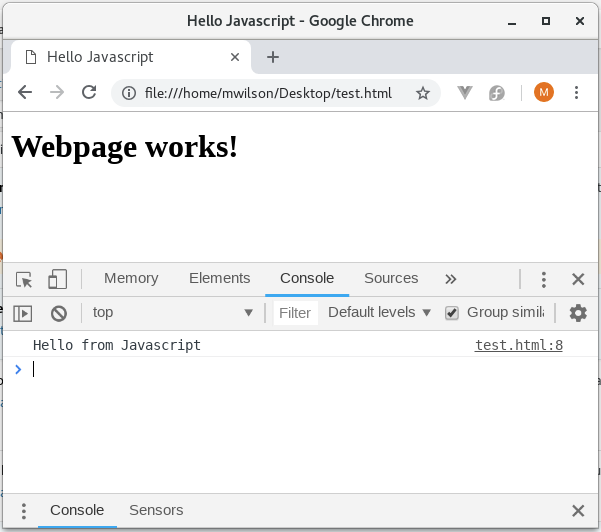

After saving and opening the file, you should see the bold title “Webpage works!” when you view that file in a browser. So now let’s add some JavaScript.

JavaScript can be added directly to an HTML webpage by adding it inside script tags <script> /*javascript code goes here */</script>. There is a function console.log that allows us to output values to the console. Let’s use it in our first script. Let’s insert a set of script tags inside our previous HTML code with console.log('Hello from Javascript') inside. Our completed HTML should now look like:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello Javascript</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Webpage works!</h1>

<script>

console.log('Hello from Javascript')

</script>

</body>

</html>

Now open that page in a web browser. With the console open, you should see the words “Hello from JavaScript”.

Inline scripts are fine for smaller sections of code, but they are not ideal for larger projects. Thankfully we can solve this problem by using external scripts. To demonstrate this, let’s write some JavaScript in a separate file and then include it into our page with the same script tags as above, but with one modification.

To do this, we can use an attribute within the script tag which looks like: <script src="file.js"></script>. The “src” stands for source, and it defines where the webpage can find the script file. So to add an external script to our example web page, let’s save a JavaScript file in the same folder as our HTML file and name it “example.js”. Using our text editor again, add the console.log('Hello from Javascript') . Let’s also add another line, console.log('I am an external script'). So our example.js file should look like:

console.log('Hello from Javascript')

console.log('I am an external script')

Once that is done, we need to go back to our HTML file and update our script tag. By having the two files in the same folder, all we have to do is add our Javascript file name to the “scr” attribute. So your HTML file will look like:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello Javascript</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Webpage works!</h1>

<script src="example.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

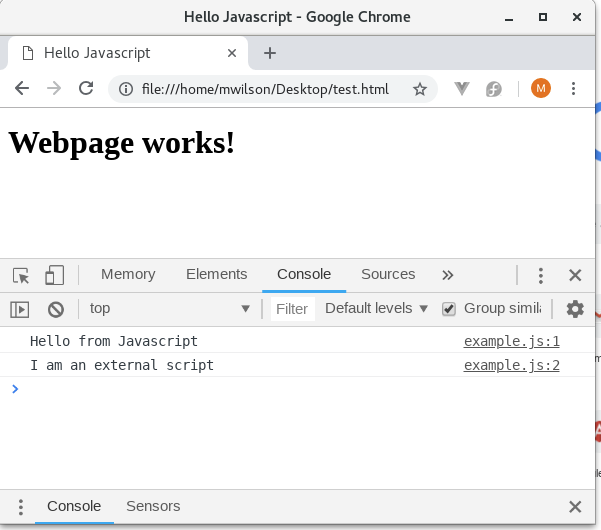

As long as we entered everything correctly and the files are in the same folder, opening the HTML file with a web browser should look like:

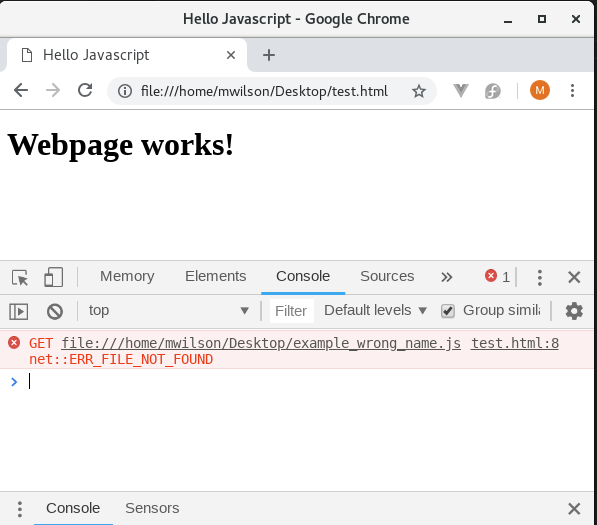

You can see both of the console.log statements printed their values into the console. It’s important to note, however, that if the file was in a different location or named incorrectly, our browser would try to load the file but would return an error instead. This would look like:

And our console.log would never show, of course.

That’s all there is to it! I also added a special file to this page, and it is logging a question for you in the console. Please take a look and answer the question in the comments.

please feel free to checkout out one of my projects AEROTRAKS.COM